Q&A with:

Oneohtrix Point Never

Daniel Lopatin didn’t move to New York City to become a musician. After losing a job in his hometown of Boston, the artist known under the opaque alias Oneohtrix Point Never attended graduate school at Pratt. There, he studied to become a data archivist, to handle metadata, to organize the exponentially growing swarm of information that humans use to understand the world around them. Lopatin never worked as an archivist, but his fascination with data and how people use it informs his work as Oneohtrix Point Never. His Warp debut, R Plus Seven, plays like a transmission from inside a flickering digital library, an artifact from the accidental collision of Baroque choral symphonies and ’80s science fiction soundtracks.

As an experimental electronic musician, Lopatin has only deepened his curiosity about the aggregate of human activity that’s always vibrating out in the world. To him, genre isn’t just a set of aesthetic constraints. It’s a way to describe the sum total of human behavior that coincides with a certain kind of music. EDM sounds a certain way, but it also groups together stadium raves, long morning runs, and frantic late night study sessions. Music doesn’t exist in a vacuum, but in all the spaces people use it to augment experiences.

Like swaths of data that help illustrate the way real people live real lives, R Plus Seven is at once abstract and intensely personal. Skyping between Chicago and New York, Lopatin and I spoke about what it’s like to make an electronic record with no palpable references to anything outside itself that still manages to be intimate, sincere, and emotionally powerful.

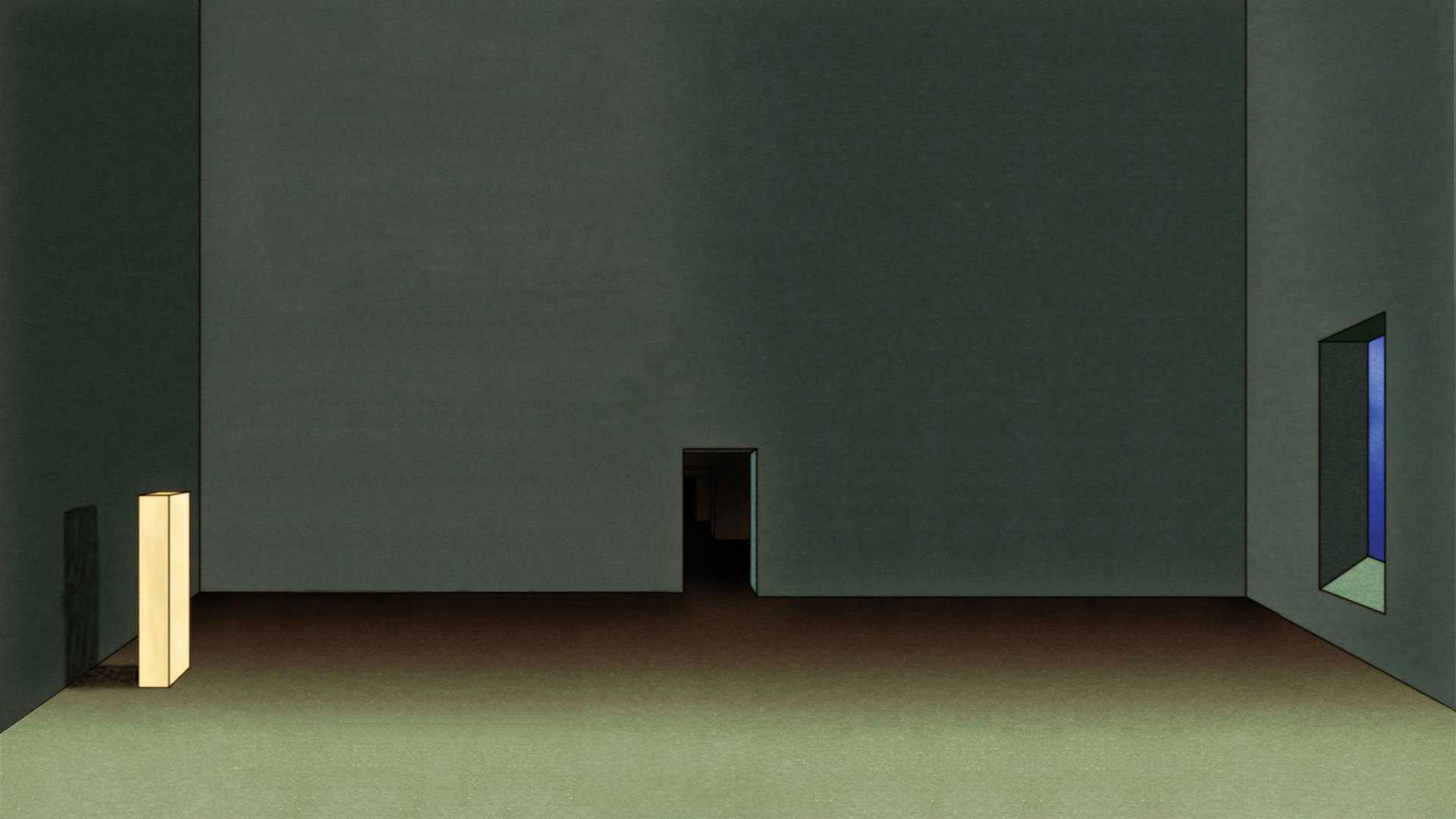

Congratulations on the record. I’ve been listening to it a lot. It almost sounds like it’s in surround sound even though it’s in stereo. If you could design the ideal physical environment for someone to listen to R Plus Seven, what would it be?

I guess I would just mess around with 5.1. There’s a lot of really specific sound moments that you could kind of place in a stereo image or stereo field in front of you or behind you or slightly asymmetrically over to one side or another. It’s not necessarily a very vertically dense record. There’s a lot of sound moments or objects.

I actually have synesthesia, so they really do look like objects. A lot of moments on the record remind me of shafts of light.

That’s cool. One of the early names for the first track on the record was actually really long—it was, “Coptic Angel (0.00 Cindy Call Me Up)”. But Coptic light is the light that comes through stained glass windows.

Yeah, I definitely see cathedrals in there. It seems like there are references to sacred music. Were those intentional?

Yeah, the palette was definitely intentional. I don’t think there’s ever a moment where I’m just like, “Yeah, that’ll work.” That has been the case in the past, for sure, but I think with this record I was like, man, everything’s really naked and in clear view so I want it to be very specific. When I make a decision, I want to have a sense of why even if I don’t necessarily want to tell people why.

With albums like Replica, it felt like you were making music through a process of destruction, of stretching things out and distorting them. This one feels more like you were building sounds from the ground up. There’s more negative space. How was the process of composing R Plus Seven different from earlier work?

In the past with things like Replica, I would compose music around non-musical sound and the non-musical sound would suggest to me what I had to do melodically. With this record, it was more of an inversion of that process. I would sit down with an organ sound or a piano sound and just kind of wait to get hit in the head with a motif or an idea, a chordal idea, or just a line. Or whatever. Music, you know? And then deal with space and sculptural things around that. It kind of flip-flopped.

There’s an embarrassment in the process associated with sitting down and waiting to be inspired musically. I found that to be embarrassing, personally. I was very uncomfortable with the idea that I’m just going to get struck in the head with some sort of idea out of nothing. To me, that felt like a cliché from the myth of art, like, an apple falls on your head and then you paint the Mona Lisa or whatever. I was sort of like, “really? I’m going to fucking just sit here and do that? That’s not me.” But it had just become tedious, doing things that were informally formal and procedural all the time. I relied on procedures to suggest how to build up music. It became a comfort zone for me to work that way. I was like, I think I’m scared of just writing music for music’s sake, lyrically; in other words, something that you can sing or whistle. Because I had a certain kind of discomfort with that mode of writing, I was attracted to it more. I was unfamiliar with it. It just seemed weird and lurid and spooky so I was like, okay, I’m just going to do it.

Did that kind of writing get easier as you went along?

I don’t think it got easier. I think there was some kind of explosion of things at some point halfway through and then nothing for a while and then like, oh, okay, I have clarity. But I don’t think it got easier.

I really like the video for “Problem Areas”. How did the collaboration with Takeshi Murata come about?

Takeshi already had these beautiful still lifes that he had done. The video is more or less a documentary-style collection of cropped or zoomed or rotated views of these still lifes that he already had. We didn’t need to work together on that. I was really, really taken by his still lifes way earlier in the process. There’s even a reference to Murata in the liner notes of the record. There’s a track called “Still Life” that’s about his work. We kind of had known each other for a while. We both were eager to hook up on something that made sense.

Neither of us really thought of “Problem Areas” as a video, necessarily. What we wanted to do is we wanted to make these wiggle .gifs with those images to skin the walls of a cube on the website. That was the first thing. We did that and it just kind of wiggled around, and it was awesome. Inside that cube was a Soundcloud embed with a track. Then the night before the track went up, the record label was like, “Oh, we’re going to put ‘Problem Areas’ on YouTube as well. Do you want to just have a still image or something?” And somebody had done some kind of mockup of that using Ken Burns pans across a still image of Takeshi’s. And then Takeshi at like 11pm was like, “Nah, I don’t really like that.” They were like, “We’re doing this in four hours.” And he was like, “Cool,” and he did [the video] in the middle of the night, basically.

A lot of the album sounds like it comes from that same place—sounds that hint at something organic but are clearly artificial.

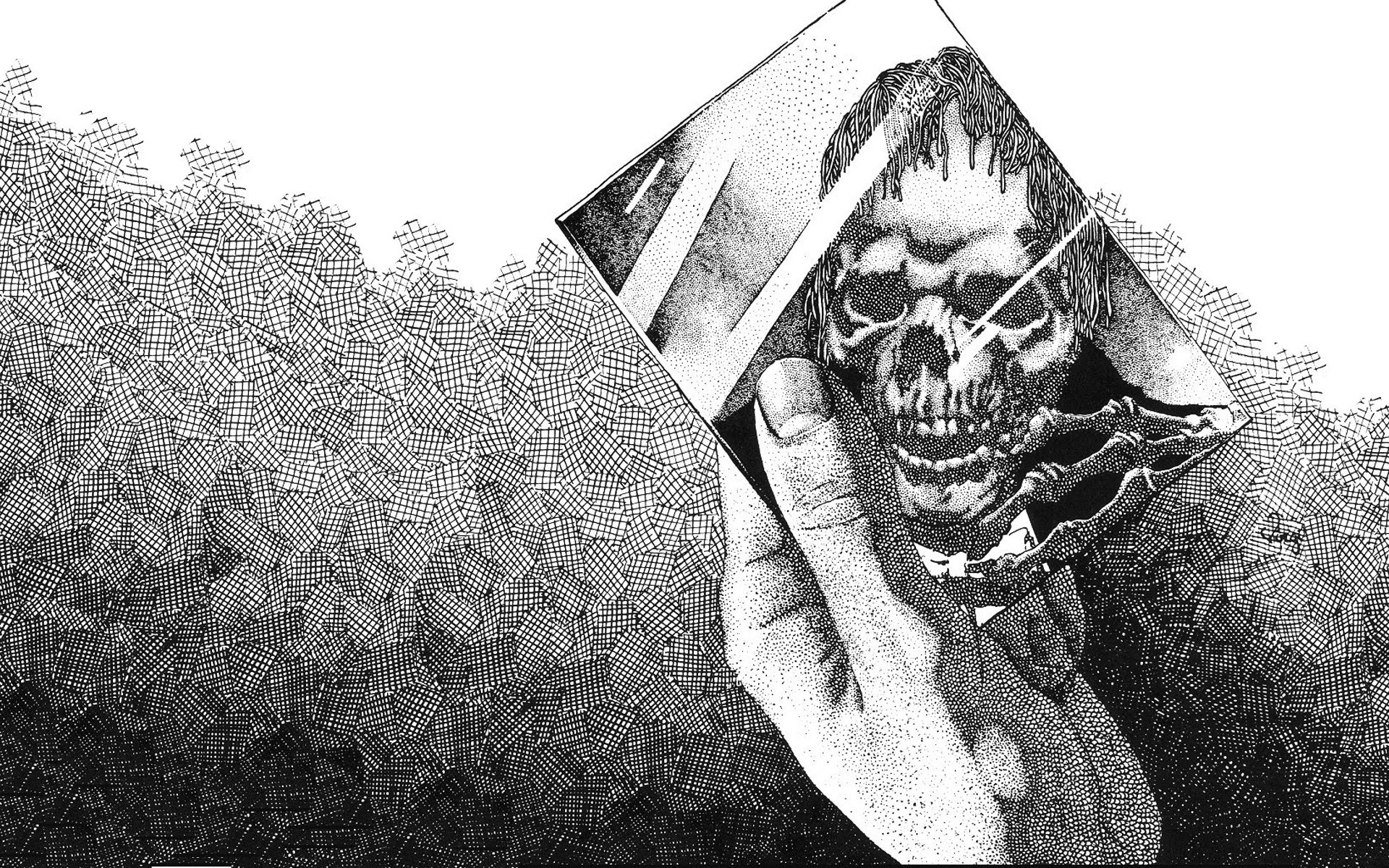

Maybe we work in a similar way with process. There’s an interview with Takeshi discussing that particular series of images, and he says that it’s really weird to start from this infinite plane in terms of CG. You just start from nothing. You have an endless vista, basically. And then you have to start defining rules and constraints and limiting this infinite plane, which is obviously very different than working on a canvas with paint. I think it’s that tableau-style approach where you really are being very particular about a collection of objects and the secret life that they share together and how they communicate ideas about themselves. That feels like something I was really trying to do a lot with the music on the record and why Takeshi’s images felt very close. I was so fond of them because they have this beautiful tableau-like experience of inanimate things where it always brought into question how those things interrelate and what, if anything, is really going on there. There’s this dread beyond the stillness of these things that is so lurid to me.

How did you come up with a sonic language to create that kind of experience?

I think I just kind of work intuitively. There is some sort of through-line that I can feel, but it’s not definitively something. A lot of the time it’s just technical rules or aesthetic rules that limit me to a scene. Utilizing genre…I don’t know how to describe it. I guess the easiest way for me to say it is, to me, genre is very important because it is very limiting. That limitation is something that I use as paint to describe how I see the world through music. That people would make lifestyle choices around music or behavioral choices or exercise to certain things or have certain music represent a sensual aspect of their lives, all of these decisions limit and define that music, and define the experience of that music.

To me, that’s the first step in making the music that I want to make: creating a picture of how all those things exist at the same time, not simply, oh, this is this and that is that, but what is a picture of all those things existing together, the way the world allows them to? What is the sound of the frictions between those decisions? The layers of things happening? Things that are incidental, things that are purposeful, things that exist in your field of hearing that don’t have to do with what you want to hear. Things that you buy to mute the world around you. I try to paint a picture that’s one level removed from those choices and show them together in a space. That’s my ideal music. It would represent how strange and incongruous all of those things are together in this weird cornucopia of human choices.

If I was in a store, there’s music being played that’s been picked by the store to put me in a certain mood, but there’s also the shuffling of things on shelves, there’s also conversations that I may or may not be privy to that I hear, that I pick up, there’s the sound of my own bodily situation at that moment. To me, all of those things are equal. When we stratify them, what we’re doing is making sense out of our lives. We’re making it easier to cope with. I don’t want to do that when I make music. I want to be more honest. I don’t want to stratify those things. So how do I paint a picture that characterizes the way I see the world?

What is it like to put out this music that is honest to you and see people in the world respond to it?

I do this thing and it goes into the world, the way everything goes into the world. Everything is subject to everything. All I know to logically do as a human being is to try to be truthful if I’m going to make art and to try to eat so that I don’t die. That’s the end of the story for me. I just don’t know. If I started trying to understand that even further, like how to bifurcate the way that I exist in the realm of the music industry, I think I would have a mental breakdown at this point. I just hope for the best. I just want people to like it and give me a chance to keep working so that I can get a little bit closer to my own personal truth about all this stuff.

Do you feel like this record is closer to that personal truth than your previous albums?

Yeah, I do. I’ve had moments where I’ve felt very far away from that and from myself and that’s okay. I’ve had moments where I’ve felt like I took too long. I’ve had moments where I felt extremely pushed, pressured, and impatient. And I finally think after a few tries that I know a little bit better how to treat myself and how to listen to myself. I took my time and I thought things through, and I made sure it was something I really believed in from beginning to end. There’s always things that you want to change after it’s too late, but I really feel much better than I have in the past.

Do you think it’s harder to make abstract, non-referential music that’s detached from a personal narrative?

I think it is my personal narrative, weirdly. I just tend to categorize things going on around me and things going on in my life in allegorical ways. I try to abstract things or stretch them out to understand them more, or freeze them to understand them more. You dim everything around a moment and you put a spotlight on it, and you give it some credit. You give it the respect it’s due as a moment. Sometimes I wish that I could do that all the time. You do it in moments in your life. You tell a story or you tell a joke three different ways in a row because you’re trying to absorb it and hold onto it and really understand what gives it so much life. It’s so cool and fun and lucky when you make music that you can weirdly freeze ideas and refine them.

I don’t know if it’s important for other people or what, but I think if I’m honest with myself from thought to expression, I need to take into account everything. If I just made music in an ABA way, I don’t think that that would be honest with the way that I think or the way I hear things, or the way that I experience things. So if my purpose is to give a truthful account of the way that I perceive the world through music, then I have to be honest. I have to admit that it’s this incongruous thing with weird ratios and strange patterns.